|

|

|

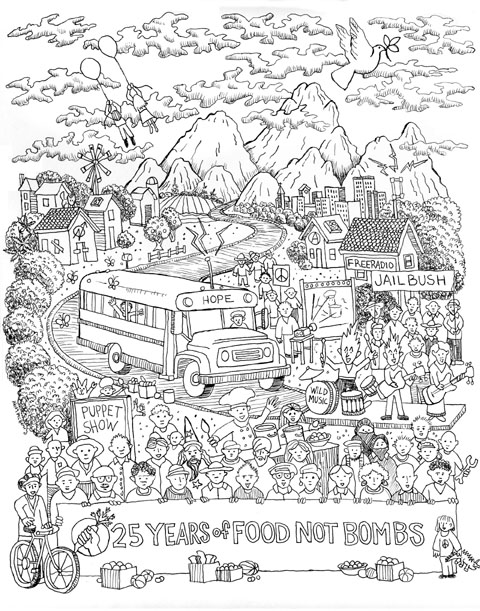

In 1980 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, seven anti-nuclear activists started a collective that came to be known as Food Not Bombs. They recovered surplus food that couldn't be sold from grocery stores, bakers and food manufacturers. This food was distributed to housing projects, daycare centers and battered women1s shelters. They also prepared vegetarian meals and shared it along with their literature at protests. Over 25 years, this small experiment grew into a worldwide movement with hundreds of autonomous chapters active on every continent, with the exception of Antarctica. The Food Not Bombs movement is unique in many ways. It's rare for political movements to cross so many national boundaries and cultures. It1s unusual for a grassroots progressive movement to survive 25 years and still be entirely grassroots. Also, from the beginning, Food Not Bombs was multi-issue and encouraged the public and activists to see that all social injustices are connected. And, while it might seem strange today, Food Not Bombs was at the forefront of focusing on building the kind of society they wanted instead of trying to overthrow the current system. These activists believed they did not need to attack the oppressors to be in conflict with the state, but by simply doing what they believed was just, the authorities would attack and try to stop them. There are several reasons why this movement is so strong. It is very empowering to collect, prepare and share free food all on your own and to do it with little money and few resources. Sharing food is powerful and magical. Additionally, when average people realize they have the power to make a difference, it can change their life. This is the foundation of social change and the authorities know it. In fact, San Francisco Police memos state that if they did not stop Food Not Bombs, the public might come to believe that they could solve social problems without government assistance. The self-empowerment of tens of thousands of people may be Food Not Bombs' greatest achievement. Every chapter shares the unifying principles of Food Not Bomb: a commitment to non-violent action, sharing free vegetarian food to anyone without restriction, and making decisions by participatory democracy or consensus. These ideals play an important role in the success of this movement. Food Not Bombs has no headquarters nor leaders and every volunteer has a say in the decisions of their local group. This leads to a strong sense of responsibility for the actions of the group and pride in what they accomplish. These lessons are often spread to other kinds of community organizing efforts. Many affinity groups addressing basic human needs and social injustice have used Food Not Bombs as a model for their organizing. Two of the founding members of the Food Not Bombs collective, C.T. Lawrence Butler and Amy Rothstein, wrote the book On Conflict and Consensus, which defines a model of consensus decisionmaking called Formal Consensus, based on their experience at meetings of Food Not Bombs, the Clamshell Alliance and the Pledge of Resistance. Food Not Bombs encourages people to start their own chapters. In 1992, Keith McHenry and C.T. Lawrence Butler, founding members of Food Not Bombs, published the handbook Food Not Bombs, How to Feed the Hungry and Build Community, with the forward by historian Howard Zinn. Over 10,000 English copies, 3,000 Spanish and 1,500 Italian editions have been sold. In 1980, they wrote " the next few years could profoundly change the world for generations and Food Not Bombs is working to make those changes positive for everyone."This understanding that the world is at a critical time in history and that average working people have the responsibility to make the world a better place is as true today as it was when Food Not Bombs started. The seven young people that started Food Not Bombs were united by the events of May 24, 1980. On that sunny spring day, over 4,000 activists with the Coalition for Direct Action at Seabrook made an attempt to occupy the Seabrook Nuclear Power Generating Station with the intent of non-violently stopping construction by putting their bodies in front of the bulldozers. As affinity groups cut holes in the fence surrounding the construction site, clouds of stinging teargas filled the air. National Guard troops rushed through the fence, beating everyone they could. Helicopters hovered above as the activists struggled to occupy the site. The next day, Boston University law student Brian Feigenbaum (eventually another founding member of Food Not Bombs), was arrested for assaulting a police officer, allegedly hitting him with a grappling hook. Concerned about Brian1s legal problems, a core group of about 30 activists formed to support his legal defense. Out of this effort grew the collective that started Food Not Bombs. Therefore, this attempted occupation of Seabrook on May 24, 1980 marks the beginning of the Food Not Bombs movement. To raise money for Brain1s legal defense, the collective set up literature tables and sold baked goods outside of Boston University and in Harvard Square, but sales were slow. An idea emerged that street theater might help. They had a poster that stated, "It will be a great day when our schools get all the money they need and the air force has to hold a bake sale to buy a bomber." The group bought military uniforms at an army surplus store, set the poster next to their table and pretended to be generals trying to sell baked goods to buy a bomber. While they didn't sell more brownies and cookies, they did talk to many more people about Brian1s case and the risks of nuclear power. Eventually, Brian1s charges were dropped for lack of evidence and the collective had discovered a great way to organize. With Brian free, the collective decided to organize its first protest to get the message across that the financial backing of Seabrook had links to the First National Bank of Boston. Many of the same people who were on the board of the Bank, which was financing the nuke, were also on the board of the utility that decided to build the nuke and many also sat on the board of the construction company building it. To the activists, this looked like the business practices that resulted in the Great Depression. To protest the bank's decision to pour money into this risky investment, they again used street theater. The activists planned to dress as Depression era hobos and set up a soup line outside the bank's annual stockholders meeting in the financial district of downtown Boston. The night before, worried that they might not have enough people to have a soup line, they went to the Pine Street Inn, the largest homeless shelter downtown, to talk with the homeless about the protest and invited them for lunch. The next day, the activists set up a soup kitchen in the plaza outside the Federal Reserve Bank, where the board meeting was being held, and, to their surprise, over 50 homeless people joined them for lunch. Many stockholders expressed anger and some laughed at the protesters. However, the homeless folks were excitedly talking with the servers and started inviting passersby to join them at lunch. Many people stopped, had a bite to eat and talked with the homeless and activists about the reasons for the protest. They took flyers and expressed support. It was an exhilarating day. While cleaning up, the seven activists decided that distributing food could be a great way to organize for peace, the environment and social justice. It wasn't long before they had rented a house together and started a regular network of food collection and distribution sites. They picked up muffins and bread at "made fresh daily" bakeries, produce and tofu at health food stores and surplus stock from the food coop. Each weekday, within hours of collecting the food, they delivered it to battered women's shelters, alcoholic rehabilitation centers, immigrant support centers, and once a week to each of the housing projects in Cambridge and some in Boston. They set up a table at Harvard Square and gave away flyers about social issues. This Food Not Bombs table became a "little town hall" where people expressed their ideas and became involved in discussions about current events. The nights were spent spray-painting graffiti for peace. Themes included white outlines of dead bodies, which founding member, Jo Swanson, used as the basis for her national 3Shadow Project2 and stencils of the image of the nuclear mushroom cloud with the question 3Today?2 Outside grocery stores they painted the slogan, "Drop Food Not Bombs." Eventually, this was shortened and became the name of the group. In the first two years, Food Not Bombs focused on its literature and food tables, bulk food distribution and building momentum for the June 12, 1982 action "March for Nuclear Disarmament"in New York City. Leading up to this event, Food Not Bombs co-sponsored, with the Cambridge City Council, three marches against nuclear arms. On Hiroshima Day, one volunteer burned the Boston phone book to dramatize that everyone listed would burn in a nuclear attack. During this time, one of the most complex events the Food Not Bombs collective organized was the "Free Concert for Nuclear Disarmament" at Sennot Park in Cambridge in May of 1982. There was plenty of free food for everyone and bands representing the ethnic mixture of Cambridge performed. There was an area with activities for kids of all ages called "The Land of the Younger Self" organized by Su Eaton, another founding member of Food Not Bombs. Artists, craft people and local peace and justice groups had tables. It was a great success and another magical day for Food Not Bombs. Over the next several years, the Food Not Bombs collective also helped organized direct actions to end the war in El Salvador, including one where 500 people were arrested for holding a "town meeting" in the lobby of the Boston Federal Building. Another founding member, Mira Brown, was with Ben Linder in Nicaragua, when he was killed by US-funded "contras". They also participated at a sit-in at the Federal Court against the draft, and they organized the Boston Pee Party, a protest against drug testing which was mentioned in Abbie Hoffman1s book Steal this Drug Test. Another action they helped organize was a protest against a "weapons bazaar" at a hotel in downtown Boston. This is an event where U.S. corporations promote the sale of weapons to the military of other countries. This particular one featured chemical weapons that were eventually sold to Iraq and used by Saddam Hussein on the Kurds. During the mid-80s, Food Not Bombs continued collecting hundreds of pounds of surplus food everyday. During the week, they would distribute it to area housing projects, progressive social service agencies, battered woman's shelters and hunger relief agencies. These groups would receive this food once a week and be responsible for distributing it. The idea was for them to use this bulk free food as an organizing tool to reach out to new constituencies. On the weekends, Food Not Bombs would cook the food making vegetarian meals and set-up tables at rallies, protests, conferences, meetings, anywhere activists gathered and serve free food, distribute literature and collect donations. In this way, they were able to support their ongoing food distribution program and pay the rent. After a short while, they were serving free food at just about every protest in New England.

|

|

PART 2 THE SAN FRANCISCO ERA |

PO Box 424, Arroyo Seco, NM 87514

1-800-884-1136

Start a Food Not Bombs group

[ MAIN MENU | More FNB Websites | Flyers You Can Reprint | Food Not Bombs Handbook ]

[

How to Start a Food Not Bombs | Events | FNB Contact List |

Home ]